In nineteenth-century Malabar, the institution of agrarian slavery was a deeply entrenched social and economic system. Individuals from the lowest castes, primarily the Cherumans and Pulayans, were hereditary bondsmen, considered inseparable from the landed property and held precisely under the same tenures and terms as the land itself. These slave castes – the Pulayas and Paraiyas in Travancore and the Cherumars were considered an inseparable part of the landed property, “held precisely under the same tenures and terms as the land itself,” and formed the backbone of the region’s agrarian economy, particularly for labour-intensive paddy cultivation and the continuity of upper-caste landlordism.

Before the Slavery Abolition Act of 1843, the slave trade operated as a formal and lucrative institution. Slaves were openly bought, sold, mortgaged, and leased. Their prices varied widely, as recorded in H. S. Graeme’s report, ranging from eleven to two hundred and fifty gold fanams depending on caste, age, and health. Religion played a decisive role in determining the fate of slaves. Campbell observed that Muslim law prohibited the purchase of free children for bondage, and slaves purchased as infidels who later converted to Islam ceased to be considered slaves thereafter. In contrast, Hindu slaves were denied the right to return to their parents, ensuring the perpetuation of their bondage across generations.

The Slavery Abolition Act of 1843 altered the legal structure on paper while leaving social realities largely intact. Implementation was weak, communication limited, and enforcement sporadic, which allowed clandestine transactions to continue. For the predominantly Hindu agricultural slave population such as the Cherumars, the Act’s impact remained negligible. Many continued to be sold in secret. Their situation often deteriorated further as they were drawn into the expanding regime of colonial plantations, where economic exploitation intensified under a new guise.

The Christian Missionary Society (CMS) entered this complex landscape following a schism with the ancient Syrian Christian community. The CMS’s initial presence in Travancore had been facilitated by a unique political circumstance. After the Travancore Rebellion of 1809, in which local factions resisted the Travancore state’s administration and British interference, British Political Residents like John Munro gained unprecedented influence, even serving as Diwan (Chief Minister). Munro, an Evangelical, actively favored Christians, elevating them to government posts and supporting missionary education. This Anglo-Syrian collaboration, however, collapsed in 1836 at the Synod of Mavelikkara when the Syrian Church, resisting Anglican attempts to control its doctrines, formally broke ties with the CMS.

This rupture proved to be a turning point. Freed from their focus on reforming the Syrian Church, the missionaries from the 1840s onwards redirected their efforts toward the marginalized lower castes. It was in this new context that, in 1847, they submitted a memorandum to the ruler of Travancore calling for the abolition of slavery. This petition marked a turning point in the politics of abolition, though it was fiercely opposed by landlords who feared that their lands would remain uncultivated. Travancore formally abolished slavery in 1855. This development coincided with the mass conversion of slave castes to Christianity and the rise of a plantation-based economy that required a steady, disciplined labour force.

The missionaries were not merely advocates of abolition but active participants in the evolving colonial economy. Many owned plantations themselves and employed the very communities they had campaigned to free. The abolition legislation dismantled traditional bondage and created a mobile pool of former slaves who were reorganized into a disciplined and wage-dependent workforce. Conversion to Christianity played a vital role in this transition. As represented in literary works such as Ghathaka Vadhom, the converts were taught values of obedience, honesty, and loyalty, which made them self-regulating and submissive labourers ideally suited to plantation work.

This transformation extended beyond the local. The novel Sukumari illustrates the global dimension of this historical process through the story of Satyarthi, The novel Sukumari provides a vivid account of this global export of labour, recounting how Satyarthi, a Pulaya convert, was transported on a British ship to Bourbourn (Mauritius) and later escaped to Australia, where he endured miserable and traumatic conditions as a miner. His story exemplifies the broader circulation of coerced labour and the integration of Kerala’s slave population into the global plantation economy.

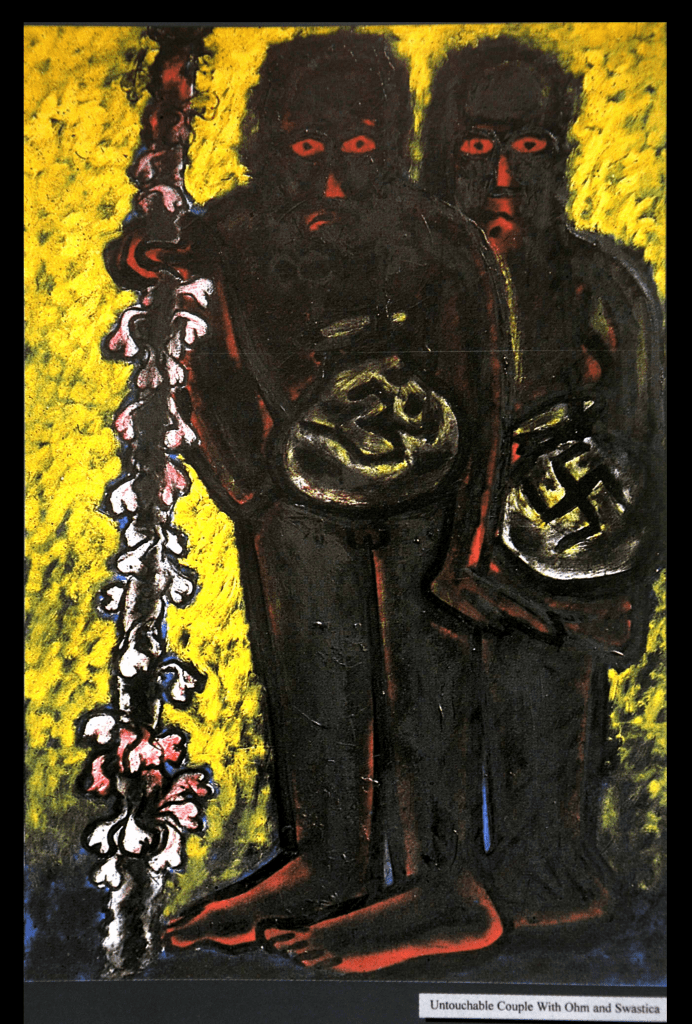

Colonial authorities and missionaries employed ethnographic tools, including photographs such as that of Marathan Pulayan, to study the physiognomy of converts and evaluate their potential as productive labourers. This intersection of ethnography, religion, and colonial capitalism demonstrates how scientific knowledge was mobilized to reinforce systems of exploitation. The Kangani system (ostensibly a contractual method of labour recruitment) further entrenched these practices. Workers from Travancore, Madras, cochin, and Malabar were recruited under conditions that fostered debt, dependency, and renewed forms of servitude despite the nominal shift to wage labour.

Marathan Pulayan is a fictional character from the 19th-century Malayalam novel Saraswati Vijayam (1892) by Potheri Kunjambu. He is a Pulaya slave, belonging to one of Travancore’s main slave castes, and his conversion to Christianity forms a key plot point. The novel describes a missionary priest photographing him at the time of his conversion; this image was sent to the West (“Bilathi”) so that British capitalists could study the physiognomy of slave castes and assess potential changes following conversion. In the narrative, Marathan Pulayan’s (assumed) murder triggers a police case. The upper-caste landlord Kuberan Namboothiri orders the punishment of Marathan Pulayan for singing while working, resulting in his death. The subsequent police investigation, though not central to the plot, illustrates the emergence of modern legal rights for slave castes while simultaneously showing how upper castes could manipulate the system through bribery.

It is important to situate Malabar’s experience within the broader distinctive features of Indian social history. Unlike classical European slavery, which was central to production and tightly tied to chattel ownership, slavery in India had always been relatively peripheral, often intertwined with caste-based social hierarchies rather than direct economic exploitation. However, regional exceptions like Kerala, with its severe systems of agrestic slavery and even reports of tribal people being sold in open markets well into the modern era, demonstrate a persistent and virulent localized pattern of servitude. In Kerala, hereditary serfdom and bonded labour represented a profound adaptation of subjugation where the lowest castes like the “Pulayas and Cherumars” functioned as the backbone of agrarian production. This highlights that the transformation from caste-based bondage to plantation labour was a reorganization of existing unfreedom under colonial capitalism instead of a simple abolition, making it both distinctive and uniquely resilient

The trajectory of nineteenth-century Malabar’s agrestic slaves reveals a continuous thread of exploitation running through every phase of reform and conversion. The failure of the 1843 Abolition Act to secure genuine emancipation, combined with missionary-led campaigns that redirected bondage into the discipline of the wage system, ensured that the majority of Hindu agrestic slaves merely transitioned from one form of servitude to another. Their mode of alienation changed, yet the substance of their exploitation persisted. The transformation of Malabar’s slave population from hereditary serfs to plantation labourers thus represents the reorganization of unfreedom under colonial capitalism, a process that connected the rice fields of Kerala to the plantations of Mauritius and the mines of Australia.

Leave a comment